The last week has seen a massive recall of Romaine lettuce, following a massive recall last year of Romaine lettuce. Why? The Romaine is possibly carrying e-coli.

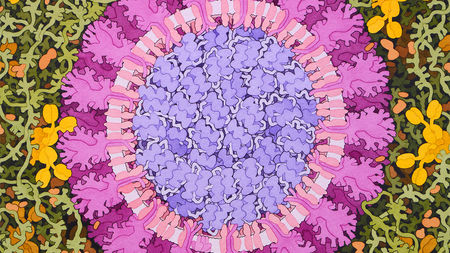

E-coli is a bacteria that is found in the intestines of cows. When cows poop and leave manure in the fields, and then it rains, you get e-coli in the water system. When humans ingest the e-coli bacteria (depending on the strain), they can get incredibly sick. But the newspapers don’t do it justice when they report on it. Newspapers say most people get diarrhea and some get further complications like kidney failure. That doesn’t really tell you what e-coli looks like, or what it does to the family or the patient. So I’m going to tell you our story.

My daughter is a survivor of E-coli. Though I do not often tell the whole story, I think it’s important at this moment to share it with you. It’s not pretty. In fact, I have said on numerous occasions that I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy.

At the age of three, on Father’s Day morning, she woke up and said she had a belly ache. That belly ache turned into diarrhea and vomiting. The diarrhea turned bloody. Though she was potty trained she needed to go back into diapers and I needed to change them every fifteen minutes. She stopped peeing. She got pale. She screamed in pain for days on end. I could not comfort her.

When her pediatrician suggested that we get a stool sample, we leaped at the suggestion, and hand delivered it to the hospital. Within a few hours we were air lifted from our home in Randolph, Vermont, to Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center. We were told that Wendy had a complication of E-coli called Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. We were told that her kidneys had already shut down and that we were being transferred to Massachusetts General Hospital. We left at daybreak for Boston in an ambulance and our lives were never the same again.

Wendy’s kidneys did not function for over three weeks, the shiga toxin in the E-coli broke down all of her blood cells. The doctors were afraid something else was wrong but could not do a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) because they were afraid she would bleed out. Her white blood count was higher than a leukemia patient. She began to have seizures, her blood pressure would bottom out, and she would be revived with epinephrine. Though it was not indicated, the doctors decided the only course of action to possibly save Wendy’s life was to give her antibiotics to kill the bacteria, though they knew that by killing the bacteria they would be releasing all the toxin at once. The doctor gave me a hug and suggested that both of us sleep in Wendy’s room that night, because, well, you know why.

She lived. Her kidneys stuttered back to working after about 21 days but were permanently damaged.

A few weeks later, they discharged a brave fragile warrior and her parents, but we barely made it home when stomach pain began again. Her intestines had closed up as a result of the scarring from the HUS. We were rushed back through three states and she had a primary bowel resection: the surgeon removed about six inches of large intestine, and she stayed in Massachusetts General Hospital for another month. We made it back to our house in Vermont in September.

I took a year’s leave of absence from my job, teaching at the vocational school in our town. Instead I became an expert in caring for my child. Wendy was also now a diabetic (her pancreas works at 15%, again a victim of the e-coli) and she had serious dietary restrictions. First, the diabetic restrictions and injections, and then the diet of someone with kidney disease: low magnesium, low sodium, low potassium. I begged to get a referral to a dietician because I had no idea what to feed my child. I made lists of things she could eat by meal, 10 possible breakfasts, 10 possible lunches, 10 possible snacks, 10 possible dinners. I had lists of low potassium foods and high potassium foods. Of course all of her favorite foods were high potassium, so I became an expert at measuring and substitution.

A stomach ache again in October, just before Halloween, where Wendy was going to be Fiona from Shrek. More of her intestine had closed, more to be removed. This time, the surgery resulted in an infection and sepsis, and Wendy coded in the PICU and had to be revived in the middle of the night. Attending physicians came flying through the doors as Michael and I sat in the waiting room, one finally sitting down next to us and said, “What the fuck happened?”

Seven more weeks in the PICU, with Wendy unconscious. Chest tubes and PIC lines. More pumps than space on the pole, so there were extra pumps in the bed. Teams of doctors and nurses and pharmacists honestly not sure what was going on. They tested her for AIDS and Cat Scratch fever on the same day. They were grasping for straws. We went through Thanksgiving without her conscious. They only thing she could do was cry. She started to improve, slowly. We had Christmas in the hospital. We couldn’t bring her home. When we asked, the Doctor said if Wendy was going home, she was going with her. We got two hours to bring her to our apartment in Boston and open up presents.

At New Years we “celebrated” in the hospital and saw the fireworks from the 17th floor of the Ellison building. The doctors thought they could release her if we stayed locally, so they released her, but she was on so many medications (24 of them, all taken in two hour increments around the clock) that her digestive system couldn’t take them all and they readmitted her before her birthday on January 9th. She had no candles on her 4th birthday cake because you can’t have open flames in the hospital.

By the end of January they released her again but she went into heart failure and was readmitted. They floated the idea of a heart transplant, but decided to wait and see. We watched the Superbowl from the PICU. She also spent Valentine’s Day in the hospital. New restrictions were placed. No more than 750 milliliters of liquid a day, I administered it in tablespoon increments. I had to measure her urine. I had to weigh her twice a day, take her blood pressure twice a day, call the doctors to adjust medication almost every day. They knew my cell phone number by heart.

By this point, we decided that Wendy and I had to move to Boston semi-permanently, that we couldn’t risk her health and the weather. So we rented an apartment in Charlestown and she went to three different doctors a week. This was March. She slowly started to get stronger. I would take her to the park, I would take her to the art museum, the children’s museum, the science museum. We walked miles in the city. She took five medications just for her blood pressure. She took two medications before she ate any meal. She had insulin shots once before bed and with everything she ate. I was a mobile medical lab in my purse. But she got stronger. She improved. She grew back muscle and hair that she had lost during her illness.

By Mother’s Day they told me she was going to need a kidney transplant, and we went through the testing process. No one in the family could be a match. A few friends tried but had their own health problems. We needed to wait for a deceased donor. She was listed in October and transplanted on the last day of January, 2009. She had just turned five. I wondered if it was going to be her last birthday.

After the kidney transplant she continued to improve. She went up up up. The doctors peeled away her medications. She went from 24 down to her current 5 medications that she takes every day. She still is a diabetic. She still needs to watch what she eats and how much she drinks, but she appears to be a healthy, active, athletic, child. We are so proud of her. And we have met a veritable army of amazing people: doctors, nurses, child life specialists, music therapists, phlebotomists, etc. I am grateful with every cell in my body for their hard work and dedication. We leaned on the strength of friends and family, of other e-coli survivors, and met other amazing organ donors and transplant recipients. And I learned a lot about myself, my husband and our marriage, that we can survive anything, even our daughter almost dying multiple times.

But to be clear, all of this happened, ALL OF IT, because of an e-coli infection.

Now you know why I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy.

We do not know how Wendy contracted her e-coli. It could have been the hamburger she ate at my end-of-the-school-year picnic. It could have been swimming in the river. It could have been eating bagged carrots. We determined for our own sanity that we were glad we didn’t know the source of the infection because one or both of us would feel never-ending guilt if it was the hamburger, the carrots, or the river.

Here’s the thing: e-coli infections used to be rare, but they are becoming more and more common. And there’s a straight line reason to the problem: growers aren’t required to test the water they use to irrigate their food crops for pathogens like e-coli. So if no one is testing for them, the only way we find out the pathogens are there is because people get sick, and sometimes they die. The Obama Administration constructed rules for the FDA to begin implementation to mandate water testing, but the new administration has tabled the testing mandate for four years. And people keep getting sick.

Farmers contend that testing water is too expensive. Well,so are medical bills. So is chronic illness. So is never getting your life back the way it was.

So what to do? Doctors have told me that if Wendy gets e-coli again that she won’t survive it. I have been considering growing my own lettuce at home, easier in a Massachusetts summer than the winter. I’m looking at greenhouses and hydroponics, grow lights and aero growbeds.

But I’m also going to be contacting the FDA to get these water testing regulations sooner rather than later. If I can keep one other person from living through the hell that we’ve lived through, then it’s worth it. If I need to tell Wendy’s story over and over again, I will.

This is too important to sit this out and wait for the regulations to go into effect in 2026. How many people will suffer and die before then, on something that can be easily fixed and seems like a no brainer?

If you’d like to read more about it, here is an article published before the latest outbreak called The Science is Clear: Dirty Water is Making Us Sick.

If you’d like to talk to me, leave me a message.