The girls and I packed and drove my hatchback up to Camp Sunshine last week. It’s a camp located in Casco, Maine, and it’s dedicated to bringing Summer Camp to kids with life threatening illnesses. Founded in 1984 by Dr. Larry Gould and Ann Gould, it was originally a camp for kids who had cancer. In partnership with Dana Farber Hospital in Boston, 43 children and their parents came up for a very special week.

The camp has now expanded to an all-year, multi-discipline program.

We were going up for the solid organ transplant/renal themed week.

It’s a program that only gets one week a year, so it’s pretty competitive to get a slot of one of the forty “family suites” that make up Camp Sunshine. We felt very lucky, except for the fact that my husband couldn’t join us. Instead, I was allowed to bring one extra adult with me, so I asked my friend Kelly who enthusiastically agreed. As she was driving from another state, we agreed that we would meet at the front door.

Day 1:

It turns out, there are three doors:

And, I might add, they use a LOT OF YELLOW. Everywhere. On everything.

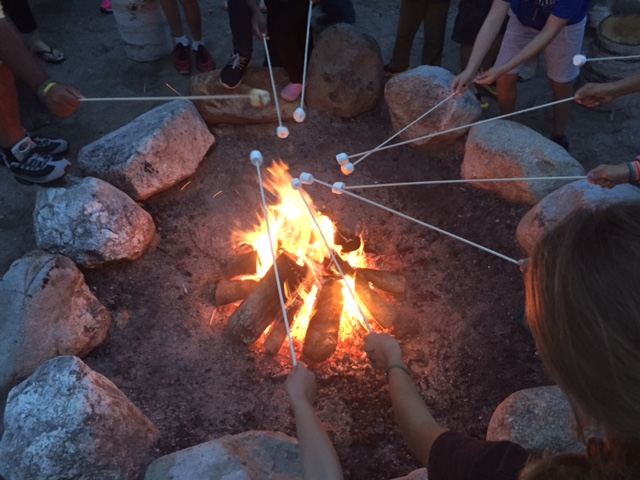

We each tried a different door, because, well, you just have to given the choice. We arrived at the front desk, had an incredibly easy check in and then were told how to get to our suite, and that there would be volunteers to help us move in, and to make sure that we used them. There would be a short reception, followed by dinner, followed by an introduction, a show, then a family bonfire and marshmallow roast.

So we got our stuff and headed to the suite, which consisted of a large room with bunkbeds and a futon, and then an extra bedroom. The girls, of course, wanted the bunk beds which was fine by the adults. There was a microwave and a small refrigerator. The bathroom was spacious. It was just about everything you needed for five nights away from home.

The volunteers were there. I want to say the volunteers were EVERYWHERE and are the heart of the organization. They start in age from high schoolers and go all the way up to retirees. They are there with your bags, they are there to serve your food, they are there to be camp counsellors to your kids, they are there to take your tray. They help with set up and break down, they sit with you at meals. Quite frankly, they are the best part about Camp Sunshine.

I’m only on day one, so let me tell you when I knew it was a special place. Yes, the dinner was good, so was the show. We were introduced to the Opening/Closing Song: “Hands Up” by Ottawan, complete with obligitory dance. The juggling show and performer were both awesome.

But it was after all of the introductions that we got to go out to the bonfire and roast marshmallows. There was a little girl, who became one of my favorites over the course of the week. She had an oxygen tank and tube going to her nose. The tank was wheeled around behind her. She and her parents negotiated unhooking the oxygen tank so she could get close enough to the bonfire to roast the marshmallows. The look of pure joy on her face showed me what this camp really was all about.

Day 2:

Day two arrived bright and early. We had to arrive in time for the Camp Sunshine Chant that opened all of the meals. After breakfast, we had to sign in the kids to their respective camps. Penny was in the 6-8 year old camp. Wendy was in the 9-12 year old camp. I was a little nervous for both of them, because this was a new place with new kids. They did not share my apprehension, however, and got right down to the having fun part of camp: Arts and Crafts, Pool Swimming, Kayaking, and their respective games rooms.

The parents, on the other hand, had to do some team building exercises. We were divided into three groups, and we had to come up with a team name and a team song. We had to practice the song and then perform it before the other adult groups and two teenage groups that joined us later. I’m not really into that kind of touchy-feely-joiny stuff, but there I was belting out “JOY(pump it up pump it up) and PAIN, CAMP SUNSHINE, NO RAIN” to the tune by Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock. Yep. There I was. All this in the quest to win the “Loving Cup Award.”

Spoiler Alert: We didn’t win.

The afternoon was much the same schedule for the kids, but the parents had a discussion group where we all came together to talk about our kids and our concerns. The first day was basically just introductions because there were so many parents there. I was blown away at all of the kids, all of their medical necessities, and how each family dealt with those issues in their own way. They looked at these meeting times as a way to discuss things that had been on their mind for the last year, many of these families coming back multiple times and giving the group a family feel. The Social Worker, Nancy, had been at Camp Sunshine almost since its inception, and was really excellent at facilitating the group, which could sometimes veer off into discussions before introductions were concluded. It was the first time in a long time that I felt like Wendy’s medical conditions were rather minor compared to some of the other families in the room, who also battled genetic disorders, cancer, multiple organ transplants, and rejection episodes in their past.

That evening was the masquerade dance. All the kids dressed up and danced like there was no tomorrow. Lots of the adults did too. Not to worry if you didn’t have a costume, there was a WHOLE CLOSET dedicated to costumes, in all shapes and sizes. Penny was the Queen of Hearts, and Wendy was the Cheshire Cat. I was a knight, and Kelly was a hula girl. Lots of the volunteers came with their own costumes, of note, the three little pigs, Prince in his Eighties era, and lots of superheros.

Day 3:

This day consisted of the other events mentioned above, the camps, the parent discussion groups, and the wonderful meals. But this day, day three, was the day of the Talent Show.

The talent show makes a person feel like they are in one of those big hotels the Catskills, where talent is loosely defined and highly celebrated. It was arranged by age, so the four year olds went first. One four year old laughed into the microphone and was applauded. The six year olds were a little more organized. Penny and friend did a “dance” routine. (note the air quotes). There was also ear wiggling, paper airplane making, and joke telling. By the time the show got to the teenager group, you had people who had planned a talent and were able to execute it on stage: good dancing, good singing, an adoring crowd.

Everyone left feeling validated, having laughed a lot and cheered a lot. We collapsed into our beds.

Day 4:

This was the day we were all nudged out of our comfort zones.

In the morning, the kids all had their normal camp activities. Kelly and I decided to go to the lakefront and take out a kayak. We kayaked out and around, and then we landed on a little island. We decided to beach the kayak and go swimming. I talked Kelly into swimming around the island (it was small) and it took some doing, but she agreed. It was super fun, and how often can you say you swam around an island?

We met the girls and it was “Afternoon Family Time” before the big evening activities, so we decided to go off campus and we travelled to the LL Bean Flagship Store in Freeport Maine, with a side stop for ice cream. Penny and Wendy got winter coats. It was nice to get out from camp for a little bit and see that the rest of the world was still spinning.

Then we all arrived back, and it was time for Wendy to do her overnight camping adventure without us. She and the 9-12 year olds travelled to the yurts on the other side of the camp and had a cookout and sleepover. She and I negotiated ahead of time what she was going to do about her diabetes, and so she periodically updated me with blood sugar reports and pictures of food. It was a great to know she was on top of things as she was the only diabetic in the whole camp.

Penny, meanwhile, got to stay up late and watch a movie with the 6-8 year olds. They watched Zootopia, ate popcorn, and felt like badasses for being able to stay up until 10.

The parents had a lovely dinner that was kid-free. Roast beef, salmon, lots of veggies, special fancy sodas (Camp Sunshine is a dry camp.) Then they were encouraged to sing karaoke, and lots of them did. (You’ll notice I said them, not we.)

An excellent night, giving everyone some independence, and allowing them to build friendships without baggage. It was much needed.

Day 5:

This was the last full day of camp. Everyone knew it. The kids prepared for the closing ceremony. They built wish boats. Everyone started to worry that it was all going to be over soon.

This was the day that a lot of the parents started their own conversations about their kids, outside of the parent meeting. This was the day that I learned the most about what other parents thought, how they really identified themselves, what they worried about. We compared immuno-suppression regimens, 504s (medical needs documentation for schools) and after-school activities. I was surprised that no other kids did the American Transplant Games, and that no other parents were on Family Advisory Councils at their hospitals. We spoke about these things over an amazing barbecue lunch on a beautiful summer day.

Then the time came for the wish boats. Each kid designed a boat that they would launch at the pond while the Camp Sunshine Song played. We gathered around the pond waiting to light the boats at dusk:

Then, wishes were made and the boats were lit and launched:

Then we all filed into the Entertainment Hall for the closing ceremonies, where each age group made a presentation. The parents also did their group cheers again (Yay). There was a slideshow of all of the events from the week. It ended with the “Hands Up” song in closing. Actually, it ended with “That’s What Friends are For” and lots of tears.

Day 6:

We woke up this morning and said say goodbye to Camp Sunshine. We were given a directory with family photos for each family at camp. We made lots of promises to keep in touch with certain families. Maybe some of those promises will be kept.

Overall, it was a good experience, and I can see how it would be even more beneficial to families who feel more overwhelmed or isolated than we do.

If you know of such a family, I encourage you to direct them to this camp. Here is the website:

Also, if you are looking for a worthwhile charity to donate to, I can’t think of a better one that gives families a much needed break from their daily medical struggles. Take a look at the website to see happy faces.

Most of all, I encourage you to sign up to be a volunteer, because I truly believe it will change your life.

May we all be so lucky to have an experience in our lives as Camp Sunshine. It highlights the best of humanity, that of helping sick kids feel normal.